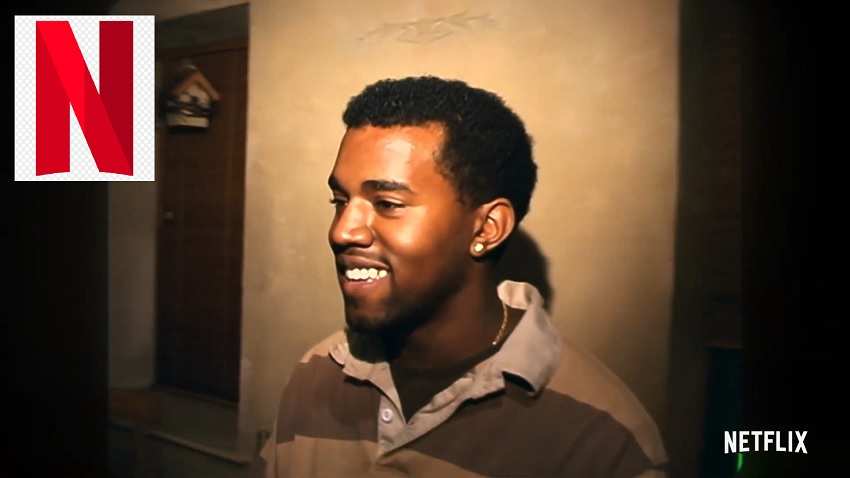

Netflix’s docuseries Jeen-Yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy is here and it’s rocking

The first part of Jeen-Yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy, a documentary trilogy on musician Kanye West, is now available on Netflix. The documentary was made by West’s pals Clarence “Coodie” Simmons and Chike Ozah, who are known as Coodie & Chike. It covers the tale of West navigating the music industry throughout his life.

Kanye West wasn’t always that well-known. He was an ambitious producer and rapper in 1990s Chicago with infinite skill and promise before threatening Pete Davidson, running for president, marrying into the Kardashian family, cutting into Taylor Swift’s speech, or calling George W. Bush a racist.

“Jeen-Yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy,” a Netflix docuseries, follows West’s meteoric ascent and subsequent missteps, stitching together more than 21 years’ worth of film recorded by the artist’s pals and documentarians, co-directors Clarence “Coodie” Simmons and Chike Ozah.

The four-hour-plus docuseries, which will be aired in three parts over the next three weeks, the first of which, “Vision,” will be released on Wednesday, is not a polished Kanye extravaganza. West was in in the loop during the production process, according to Coodie & Chike, but this is not a Ye-approved final cut. That is precisely why it is worthwhile to watch.

The progression of West’s music virtuosity, his outsized sense of self, his continual urge to accomplish more, and his mental health difficulties are all explored in this fly-on-the-wall series, which is calm and subdued in compared to its subject. When West was 21, narrator Simmons began recording him because “he saw promise” and intended to produce a documentary in the vein of “Hoop Dreams.”

“Jeen-Yuhs” is a frank, open, and empathic look at the guy behind the platinum records, public meltdowns, and tabloid frenzy. Even when West, at the height of his success, neglects the director, Simmons supports his buddy, but he also portrays West’s difficulties behind the scenes as he loses his way following the loss of his mother, Donda, in 2007.

The docuseries is around the rapper’s relationship with his mother. She’s frequently seen at his side, cheering him up while keeping him grounded. “You’ve got a lot of confidence and you come across a touch arrogant even if you’re modest,” she tells West as they sit in her apartment, West’s career just taking off.

He is deafeningly quiet, absorbing everything in. “However, it’s critical to remember to stand on the ground,” she adds. “You may be in the air and on the ground at the same time.” That’s what I assume it means when they say, “A giant may see nothing in the mirror, but everyone else sees the giant.”

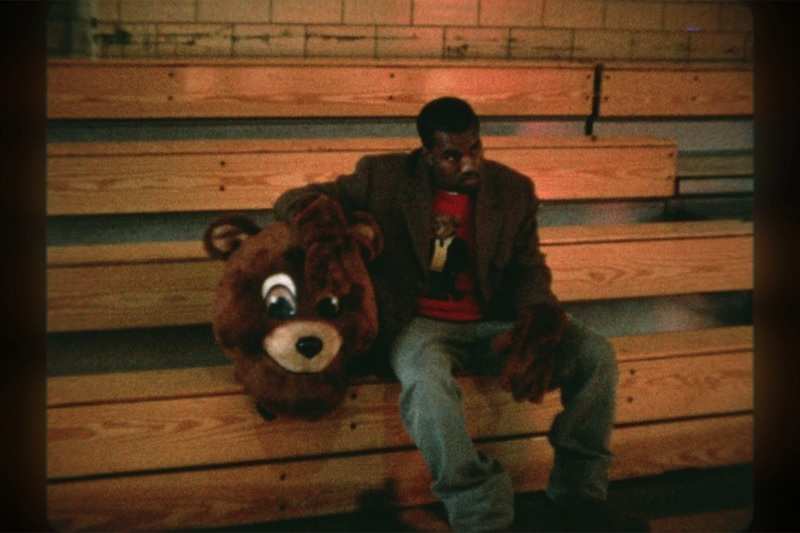

Behind the scenes, Act I features Common, Rhymefest, Jermaine Dupri, Mase, Talib Kweli, Mos Def, Damon Dash, Memphis Bleek, and Jay-Z, among others. As a sought-after producer, West is more in their sphere of influence. Smoke, flip phones, cassette tapes, Snapple bottles, and Kanye’s mouth retainer, which he pops out every time he raps over a track, abound in the studio scenes.

“Act II: Awakening,” which starts Feb. 23, follows West’s journey from top-tier producer to iconoclastic, genre-bending rap musician, one who would go on to become a dominant figure in the pop world, in the 2000s. His artistic vision had finally been recognized, but the attention had caused him to lose his footing, especially after his mother’s death.

Simmons records his suspicions that his estranged buddy is suffering from mental health difficulties in “Act III: Awakening,” and his fears are confirmed when the two reconcile on a trip to China to work on West’s fashion line. The clip of West addressing his Percocet addiction and bipolar episodes is harrowingly candid.

In many ways, the series attempts to reconcile the Kanye of those soaring early years with the bizarre figure of subsequent news reports: Kanye in a MAGA hat hugging Donald Trump; in an interview with TMZ the rapper declared that 400 years of slavery “seems like choice”; West’s presidential bid.

“It was tough to see Kanye on TV knowing he had mental health concerns.” They were calling him insane, but it appeared to me like he was pleading for assistance,” Simmons recounts, noting that, while West has always irritated certain people, “for the first time it felt like he had truly lost the people.”

Despite this, he and Ozah remained loyal to Kanye in good times and bad. “Jeen-Yuhs” is a tender account of the voyage.

‘jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy’

Original Network: Netflix

Release Date: Streaming Now, Act 2 starting Wed., Feb. 23

Rating: TV-MA

Kanye makes several references to his mental health difficulties as he goes about his increasingly bizarre business. Some of them are adorable, such as when he tells a group of designers that he wants his shoe to slim him down because he’s 35 pounds overweight as a result of his medicine. And some of them are just scary.

“Have you guys ever been handcuffed and taken to the hospital because your brain was too big for your skull?” he says at one point, shattering the unholy calm of his possible real estate partners, who appear to have just returned from human blood transfusions. “No? “All right, I’ve done it.”

He then goes on to inform these individuals that he took medicine to “convert foreign into English,” becoming increasingly angry and disoriented in the process. Coodie does the only right thing as the developers look at him with cold, moneyed scorn. He turns off the camera.

Coodie resorts to cliché as the documentary finishes at one of last summer’s Donda listening parties. “I still see so much of the person I initially put the camera on 21 years ago,” the filmmaker admits, unconvincingly. You can see he’s straining to come up with a meaningful, calm way to conclude his life’s work.

A life’s labour, on the other hand, is not linear—it unravels and corrects itself. The majority of your life’s work is a fiction that propels you forward. For Coodie, this entails keeping an eye on Kanye. The concept of “life’s work” appears to have turned into a disease for Kanye, destroying him from the inside out.

Whatever else might be said about jeen-yuhs—its lack of neutrality, its coverage gaps—difficult it’s to see it and not feel something.